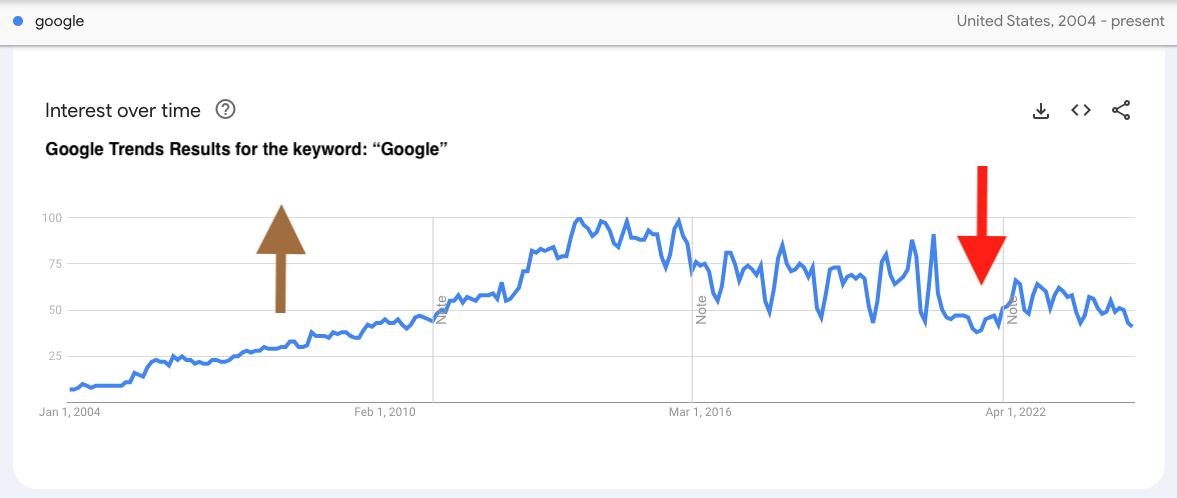

Google’s going through something, y’all—a phase. It’s not growing pains, exactly. It’s not a transition or a pivot to a bigger and brighter future. It’s difficult to put a positive spin on this one: Google is in decline, and its demise is all but certain. Its days as a go-to web navigation tool are numbered.

Oh, but don’t worry about Google. Google will be just fine. It will continue to harvest the attention of Search, YouTube, GMail, Chrome, and Google Maps users—and sell that attention to advertisers—for many years to come. The dollars will flow.

Instead, independent publishers and content creators—who traditionally viewed Google as the generous distributor of the bounty of high-quality web traffic—should begin to worry about themselves. Lord Google still commands the traffic in this fiefdom, but his noblesse oblige has vanished. He increasingly prioritizes profits over user experience, subtly, incrementally crippling the utility of his services to subjects in exchange for larger revenue hauls from the knightly classes of enterprise. And one day, perhaps, the peasants will have had enough, will deny their lord political legitimacy, will migrate, seeking the protection of a new sovereign.

In other words, Google is enshittifying, and—like a heroin addiction—enshittification is tough to break. So arduous—so counter to incentives—is deshittification that we ought to assume the Fates are in control now…and there she is, singing atop Mt. Olympus, Google’s thread in one hand, her divine scissors in the other, the goddess Atropos. We know what that means, friends. We know because Dante Alighieri told us, because Seneca and Ovid told him, because Aeschylus and Pindar told them, because Hesiod told them. We, as inheritors of the ancient wisdom, recognize Google’s trajectory for what it is, because enshittification is merely a 21st-century manifestation of a phenomenon as old as time: rise and fall.

What is Enshittification?

OK, enough with the preposterous medieval analogies and pompous classical namedrops. What’s this goofy word enshittification all about?

Enshittification, the term, has had a meteoric rise. Earlier this year, the American Dialect Society named enshittification its Word of the Year for 2023. It only first emerged in November 2022 in a blog post from the writer and social critic Cory Doctorow at Pluralistic about the degradation of Big Tech.

There, Doctorow observed:

[A]s Facebook and Twitter cemented their dominance, they steadily changed their services to capture more and more of the value that their users generated for them. At first, the tech companies shifted value from users to advertisers: engaging in more surveillance to enable finer-grained targeting and offering more intrusive forms of advertising that would fetch high prices from advertisers.

This enshittification was made possible by high switching costs. The vast communities who’d been brought in by network effects were so valuable that users couldn’t afford to quit, because that would mean giving up on important personal, professional, commercial and romantic ties. And just to make sure that users didn’t sneak away, Facebook aggressively litigated against upstarts that made it possible to stay in touch with your friends without using its services. Twitter consistently whittled away at its API support, neutering it in ways that made it harder and harder to leave Twitter without giving up the value it gave you.

When switching costs are high, services can be changed in ways that you dislike without losing your business. The higher the switching costs, the more a company can abuse you, because it knows that as bad as they’ve made things for you, you’d have to endure worse if you left.

I think this is what’s killing the social media giants.

In another think piece on TikTok’s pursuit of the well-worn path authored a few months later, Doctorow detailed enshittification’s stages, noting “how platforms die: first, they are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.”

Grim, but it checks out. Fledgling services, desperately needing users for the data that fuels validation and refinement, bend over backwards to engage and delight new users, turning them into advocates and vectors of viral spread. Typically, these entities are venture-backed, with investors looking at growth as a primary metric of progress during the early rounds, even all the way up to the IPO, meaning that startups are incentivized to aggressively lose money in pursuit of customer acquisition and retention.

So the service must be great; only great services even have the chance to become dominant online platforms like Uber, Netflix, and Amazon, who famously lost nearly $3B over a decade before turning its first profit. And, while recognition of one’s greatness is undoubtedly rewarding, the objective of the startup game is the wealth that greatness enables. Greatness is a means to an end, a stage, after which monetization takes priority, and maybe some of that greatness is sacrificed. And, while it might seem like just a taste—just a little indulgence, we’ve earned it—at first, that initial move to degrade utility is a Faustian bargain. The customer-centric muscles atrophy, and the lust for revenue builds to the point that once great tech companies are now only great at rent-seeking.

Thus, the quest for wealth drives the very innovation that it buries underneath six feet of banner ads, our heroes get fat and lazy as the next generation’s heroes emerge in the vacuum, the Fates spool and measure and clip our threads, and the world keeps turning.

Google's Journey Through Enshittification

It’s wholly unsurprising that Google is a prime example of enshittification. Once a scrappy brawler from the mean streets of the early web, Google emerged victorious in the battle royale of the search engine wars at the turn of the century, besting formidable opponents such as Lycos, HotBot, AskJeeves, Inktomi, AllTheWeb, Overture, and AltaVista in fierce combat.

By 2004, after much consolidation in the market, there were just three competitors left. The great search innovator, born to search from inception, Google found itself up against two colossi of tech’s recent past: Yahoo, the web native that came late to the search party with a few splashy acquisitions (including Inktomi, Overture, and AltaVista), and Microsoft, the PC revolutionary of the late 20th century whose roaring success with operating system and office productivity software businesses enabled a vulnerability to what founder Bill Gates called the "Internet Tidal Wave" in a legendary internal memo designed to drastically reset corporate strategy.

The Microsoft of 2004 was already an enshittifier, predating the term by decades but following its formula conscientiously. Yahoo’s acquisitions, particularly search ad pioneer Overture, were deliberate enshittification plays, leveraging the portal’s massive directory traffic to extract revenue through pay-for-performance search.

On the back of its superior search algorithm, PageRank, Google won the search engine wars, eclipsing the field with its speed, accuracy, and user-friendly interface, but enshittification was already underway. It’s easier to delude yourself into believing the lunch is free before the bill arrives. In 2000, Google launched AdWords, which allowed businesses to pay for prominent placement in search results. This move created a powerful revenue stream that would grow over time. Google protected its search engine’s utility by incorporating relevance metrics into the ad auction system, rewarding higher quality and better topical compatibility content with lower costs per click for top positions, an improvement in user experience over Overture’s strict highest bidder model., but uglier compromises were on the horizon.

The acquisition of DoubleClick in 2007 significantly expanded Google’s advertising capabilities, integrating sophisticated tracking and targeting technologies that would later contribute to concerns about privacy and data exploitation. The purchase of YouTube in 2006 and the launch of Chrome in 2008 further extended Google’s reach, embedding its services deeper into users’ online experiences.

Impacts on Independent Publishers and Content Creators

Another enshittification milestone came in 2011 with the Panda algorithm update, which purportedly aimed to demote low-quality content and improve search result quality but disproportionately affected many small publishers and content creators who relied on organic traffic. Subsequent updates, like Penguin in 2012 and Hummingbird in 2013, continued to refine Google’s algorithms but often left smaller players scrambling to adapt.

In recent years, the shift has become more pronounced. As we discussed in detail in our previous Google document leak article, independent publishers have found it increasingly difficult to compete as Google prioritizes its properties and those of large advertisers. The introduction of features like "People Also Ask" and rich snippets has also siphoned off traffic, keeping users on Google's pages rather than directing them to independent sites.

And the ad space in the SERPs keeps metastasizing. Users are noticing and commenting. Popular YouTube creators Hipyo Tech and Ask Leo! have published videos on it, the latter being my introduction to the concept of enshittification.

We’re a quarter century into Google’s rent-seeking heel turn and around 6 years past the point where Google could claim “don’t be evil” as its motto with a straight face.

What should we do about it?

The Case for Diversification

Diversifying traffic sources is no longer a mere strategy for growth; it’s a necessity for survival in an increasingly monopolized digital landscape. As Google’s platform decay continues at pace, independent publishers and content creators can’t rely on the quality of their content to attract organic search traffic. Diversification mitigates risk. By spreading traffic acquisition efforts across multiple channels, publishers can ensure a more stable and resilient flow of visitors, safeguarding their businesses against the whims of a single, increasingly enshittified platform.

Moreover, diversification enhances engagement and fosters stronger relationships with audiences. Online platforms like social media, email newsletters, and direct traffic through loyal readership offer more controlled experiences to reach and interact with users. Unlike the often impersonal and algorithm-driven nature of search engine traffic, these channels allow for tailored content delivery, community building, and deeper user connections. This multi-channel approach not only drives traffic but also enhances user affinity, creating a foundation for long-term growth and sustainability that Google can’t threaten. By looking beyond Google, publishers can reclaim autonomy and build a more balanced, diversified, and future-proof digital presence.

Beyond that, consider that all online platforms worth investing in are likely enshittifiying or heading there eventually. Avoid complacency, stay vigilant, and reserve some bandwidth for regular experiments with new tactics and channels.

Alternative Traffic Generation Strategies

Here’s some ideas to contemplate:

-

Tap into other search engines. Monitor traffic from Bing, DuckDuckGo, and others. Are you getting traffic from the keywords you want and expect? If not, spend some time understanding what factors contribute to success there, and tailor content optimization for different search algorithms.

-

Use social media to build and nurture a community of people with shared interests. This means combining Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn publishing and advertising capabilities with engagement and conversation with users and other influencers. Cultivate allies by asking them thoughtful questions, soliciting their perspectives, and signal-boosting their content so that they feel obliged to help you when your content circulates.

-

Repackage your content into an email newsletter, and include calls-to-action to subscribe. This is a way to migrate your social community into a space you own comprehensively. Incorporate calls-to-action in the newsletter to encourage subscribers to share on their socials.

-

Explore syndication and content partnerships with like-minded/complementary creators in order to cross-pollinate and share audiences. Pursue guest posting and collaboration opportunities with your favorite independent publishers and content creators.

Practical Steps for Diversification

How should you proceed?

1. Audit your traffic to understand your baseline. Identify where your traffic currently comes from and assess the risks and opportunities to weigh when making strategic adjustments.

2. Develop a diversification plan: setting goals and strategies, defining clear objectives and KPIs for a balanced approach to traffic generation.

3. Refactor reporting and metrics so that new actions are tracked. Look for conversion proxies for audience resonance, such as social follows and newsletter subscriptions.

4. And don’t forget that the quality of your content and its relevance to the target audience is the foundation upon which successful diversification is built.

Wrapping It Up

As Google enshittifies, independent publishers and content creators must adapt to survive. Google's shift from a user-centric to a profit-centric approach is rendering traditional reliance on organic search traffic increasingly precarious. The once bountiful and reliable flow of visitors from Google is now often siphoned away by its own properties or large advertisers. This reality necessitates a strategic pivot for those who depend on online traffic for their livelihood.

The case for diversification is compelling. By spreading traffic generation efforts across multiple channels, publishers can reduce dependence on any single online platform, fortifying their businesses against Google’s evolving algorithms and policies. Embracing alternative traffic sources, engaging directly with audiences through social media and email newsletters, and forming strategic partnerships with like-minded creators can provide a more stable, resilient, and engaging visitor base. This approach not only attracts quality traffic but also fosters deeper connections with audiences, whose loyalty can transcend platforms.

In the face of Google's decline, the time to act is now. By implementing a diversified traffic strategy, independent publishers and content creators can reclaim their autonomy in a volatile online environment. The future may be uncertain, but with a proactive and diversified approach, we can thrive despite the challenges posed by Google's enshittification, and maybe even win the favor of the Fates, achieve greatness, and enshittify our way to a piece of the pie on the downslope.